One of the major benefits of distributed ledger technology is that it allows several nodes to connect over a Peer-to-Peer network, whereby each node has access to the same information and is initially valued the same. This means that the network does not allow for a single node to have more privileges in the system than other nodes. Arguably, this article defines decentralization as a network which allows all nodes to equally contribute to the processes while ensuring that every node can have access to and verify all information provided by other nodes. In contrast, if a subset of nodes is provided with certain unique responsibilities, based on factors established external of the blockchain, the blockchain will be automatically less decentralised. For example, defining the selection of validator or observer nodes based on a certain status in society.

Main Point: Blockchain decentralisation should allow the equal contribution and rights of all nodes in the network.

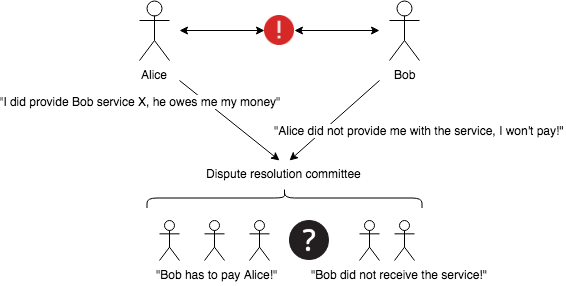

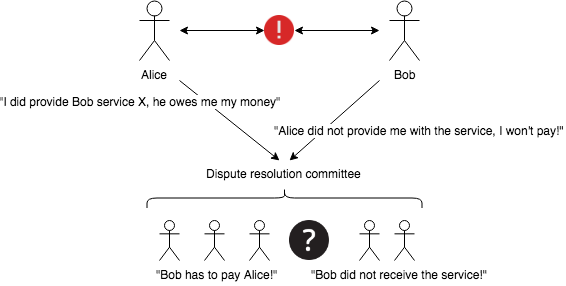

Peer-to-peer networks have to make a trade-off between scalability, decentralisation, and security, whereby it is only possible to achieve two. This article will look at decentralisation, specifically at “decentralisation of objective” vs. “subjective decision making.” Objective decision making can determine the right answer between two or several outcomes based on pre-defined criteria. For example, in Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) based consensus, the consensus is reached if 2/3 of nodes agree on the same outcome. Either 2/3 vote for the same outcome and consensus is achieved, or it is not. This is pretty straightforward. In contrast, a settlement dApp, which requires inputs from individual nodes for dispute resolution, does not allow all participants to know and verify the provided information. Two points of an argument are provided and it is dependent on the perspective of the receiver of the information to settle with either one of the nodes. This would be an example of subjective decision making.

Main Point: This post will focus on limits to decentralisation in objective vs. subjective decision making. Subjective decision making allows for ambiguity of the outcome, whereas objective decision making does not.

Crypto-projects provide varying degrees of decentralisation through their network architecture. Depending on the consensus design, blockchain state, and governance, the degree of decentralisation varies. No matter the design of the blockchain, decentralisation is limited by technical and social obstacles, including oracle data, governance, social norms, and expectations.

Oracle Data

Blockchains depend on oracles to receive information about the external world. Oracles are data sources like websites, books, measurement devices, sports scores, etc. Most of the information we consume daily has been provided by a central entity like a newspaper, TV channel, book author, or published article. On a daily basis, we must make our own determination as to what sources we define as credible and trustworthy. To do this, we take into account the author’s background, the sources on which the information is based, or in general, our relationship with that source.

Blockchains are supposed to be trustless. As such, users should not need to know who is behind the public key address of another user to verify the provided information. Therefore, we cannot base the same logic from centralised systems of informed decision making on decentralised systems. Either the information has been created on chain and thus, can be verified easily, or an off chain entity holds the information. In the case of the latter, the information has to be provided to the blockchain in a trustless manner so that they can be used for smart contract decision making. The problem is that there is no verifiable way of providing information from a centralised source to the blockchain. How does Alice know that Bob’s information is trustworthy if Alice does not know the source of the information? A decentralised system based on centralised data is no longer decentralised.

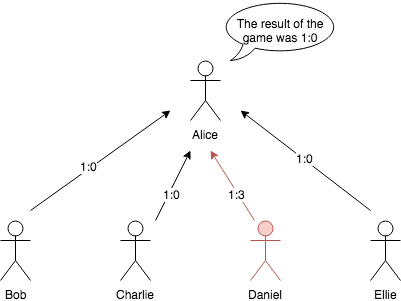

Currently, this problem can be ‘solved’ through observer nodes, whereby Alice will ask, not only Bob for his information, but also Charlie, Daniel, Ellie, and a few others. However, this is only possible for objective decision making. Observer nodes will not be trustworthy in subjective decision making. Let’s say a blockchain has to know who won the football game to resolve some pre-arranged bets. It would either allow all participants or a particular group of participants to provide their knowledge of the results of the game. So Bob, Charlie, Daniel, Ellie, and a few others will present their information on the last game. Alice might receive varying answers (because Daniel had a bad day and wanted to make up for it by winning the bet regardless of the fact that the result is not in his favour). However, the more answers she receives, the more she will trust either the average of these answers or the most frequent one. The assumption with this is that the more people who submit their result, the more accurate the outcome of the game will be.

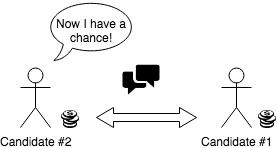

In this scenario, the outcome can still be black and white, either Team X scored, or they did not. The belief of individuals on what they think should have been the right outcome does not matter. In comparison, if Bob and Alice want to resolve a dispute, the individual perception of Charlie, Daniel, Ellie and the others on the problem does matter. Bob will say he is right and Alice will claim that the argument should be resolved in her favour. However, if the details of the dispute are not already on chain, there is no way for the dispute resolvers to settle for either Bob or Alice deterministically. They do not know whether Bob or Alice provided the right information. Resulting, the outcome will always be biased. This is why this system only works for objective decision making.

Even if the information is taken from a machine e.g. to determine the location of a package, the nodes on the blockchain do not know that the machine has not been tampered with before the recording.

Main Point: Every node should be able to verify the information on the blockchain. While a decentralised network can allow nodes, or a determined subset of nodes, to provide information to the blockchain, the information can only be accurate in the case of objective data. Subjective information provided by individual nodes cannot be verified on chain.

Governance

Governance can be defined as the principles behind decision making to manage common incentives. I am going to make the controversial claim that no blockchain is completely decentralised if it relies on off chain decision making or a hybrid approach between off chain and on chain decision making.

On chain decision making is any decision making that is based on on chain voting, whereby either any node or a subgroup of nodes who have proven that they’re trustworthy, can vote for one outcome over the other. Generally, nodes who have more to lose in the system are considered more trustworthy. For example, this can be achieved by providing a stake to the network, risking losing their ‘importance’ or investing other resources, e.g. processing power in Proof of Work (PoW) consensus. In comparison to on chain governance, off chain governance summarises any decision that is taken in one form or another off chain. This often includes the developer community and anyone else who has involved themselves in discussions. I will not go into the details, benefits, and drawbacks of either in this post. For those interested, you may want to read into Vitalik’s and Vlad’s thoughts on blockchain governance.

While I don’t take a side regarding the effectiveness of off chain or on chain decision making or a hybrid model, I believe that it limits decentralisation. In a truly decentralised environment, everyone should be able to participate in decision making, and people should be able to organise themselves to reach common goals. Governance provides the mechanisms to form groups and thus, gain power in the system. Today’s decentralised systems are built and often governed by developers. Summarising my thoughts:

Blockchain developers don’t want to directly take responsibility for governing the blockchain. They are the back-end developers of the decentralized server. They are engineers, not arbitrators, they don’t want the responsibility and they shouldn’t have it. — Vlad Zamfir

As Vlad puts it, governance should not be centralised around engineers. It scares me to see a self-determined group aiming to extrapolate the design of decentralised governance on society as a whole.

The downside of on chain democracy

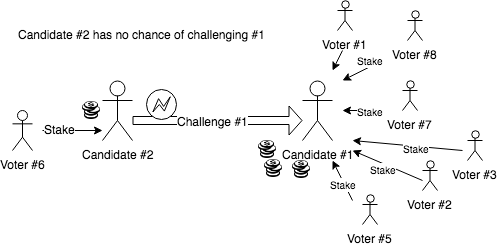

Currently, dPoS is probably the closest to an on chain democracy. It allows nodes to stake on other nodes and the nodes with the most stake to make network decisions. dPoS allows nodes to receive a large amount of stake. There is no way one individual node can vote out one of the delegated nodes (Scenario 1). However, if I do not like the decisions taken by my local government, then I can start a partition and try to sort things out in my favour. On chain governance does not allow for these kinds of actions.

In contrast to dPoS, Proof of Stake allows individual nodes to provide more stake and become part of the delegated node process themselves. This is far easier than persuading a group of nodes to stake on another outcome. (Scenario 2)

Ultimately, on chain voting would only be possible if every user has one vote. This is not the case since every user can create multiple addresses to have multiple votes. Resulting, on chain governance measures votes by wealth. The more stake a user provides, the more value is given to their vote. This merely enhances a plutocracy, whereby the rich rule the system. Therefore, effective on chain governance is currently not possible and should probably be avoided altogether.

Main Point: A blockchain is only completely decentralised if it implements on chain governance entirely. However, effective on chain governance is not possible because users cannot register their identity. Resulting, votes are measured by wealth, which does not enhance network equality.

Social

If on chain governance should be avoided in the first place because of various reasons, then certain limitations to decentralisation might be unavoidable and at the same time may not matter to the users in the system. This does not hold true for all situations. There are specific scenarios in which users probably do not mind who is making the decisions, while there are other scenarios in which transparent and tamper-proof decision making is crucial. Imagine your landlord can change your contract whenever (s)he feels like it. This would probably affect you on a financial and emotional level (stress). Therefore, it is important to you that any decision taken is discussed beforehand and within pre-agreed frameworks e.g. laws and contracts. In comparison, it does not matter to you who is serving your coffee, as long as you receive the coffee after you have paid for it.

Resulting, the average user might not even want to be involved in day-to-day decision making regarding the services they use. As much as dApps and blockchain platforms praise themselves according to the level of decentralisation in place, it might be enough for the end user to be included in the decision making of selective processes. For example, while the population of a country is required to vote for their president or party, they are not required to make environmental nor economical decisions. To establish selective decision making, the system or platform would have to decide what processes are worth involving their users in and which ones are not. This again is subjective rather than objective decision making and probably deserves a post of its own.

Overall, users are not used to having an influence on the decision making of applications. Similarly, users are not acquainted with taking responsibility for their data and passwords. While centralised applications have safety nets in place to ‘make things right’ after a user or the platform screwed up, blockchains expect their participants to take care of themselves for the most part. This might be favourable for some people, but certainly not for everyone. Making these changes in expected user behaviour is a huge step and is nothing which can happen from one year to the next. It will require a lot of understandable educational content and semi-centralised platforms.

Main Point: Decentralisation is not beneficial to everyone. If decentralised applications want to gain broad user adoption, they have to define themselves according to current schemes in usability and trust establishment.

Why should you care?

Blockchains have to prioritise between decentralisation, security and scalability. While optimisations can be made through the implementation of different designs, decentralisation has fundamental limitations for which we have yet to find proper solutions.

Limitations to decentralisation include blockchain oracles, on chain governance, and social expectations. Blockchain oracles can provide data to the blockchain, e.g. in the form of gateways like observer nodes, but other nodes on the blockchain are unable to verify the source of this information. This is a technical problem, which is easier to overcome than governance or social limitations. We might be able to better verify off chain data on chain by connecting devices directly to the blockchain. In contrast, governance and social limitations are connected with people’s mindset, which is arguably much harder to alter. Currently, people are not expected to participate in everyday decision making. Therefore, it seems quite unreasonable to expect active user participation. Reasoning along those lines raises additional concerns and problems. For example, who is allowed to decide what information should be verified by everyone and what level of decision making should be exclusive to a select group of knowledgeable individuals.

The limitations to decentralisation discussed in this post are a reflection of projects and decentralised systems that I have previously encountered. There is probably a wider range of issues pending discussion that may require further research.

Special thanks to Noam Levenson for reviewing.

For future thoughts you can follow me on Twitter here.